Monday, December 21, 2015

Monday, November 30, 2015

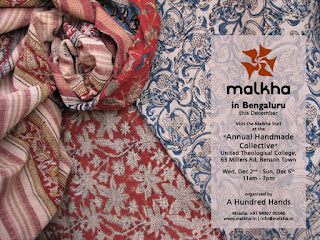

Back after a year!

Hello all, blogging again... and here is the invitation for the Malkha appearance in Bangalore, opening tomorrow:

Before this our last show was at Shantiniketan in collaboration with Bondhu Art Initiative... and before that in Kolkata at the Ice Skating Rink. Happy to say that our regular customers were able to get what they wanted from this show, as Malkha production is gradually scaling up. Another step forward is the Malkha foray into womens', mens' and childrens' garments, being shown for the first time at the Bangalore show. Here is a little girl's dress:

Tuesday, November 18, 2014

From Bangladesh

A mail from Nevine Sultana:

"I am from Bangladesh and have been wearing Malkha for some time. I went from Dacca to Kolkata to attend the Fair Trade Fair only to buy Malkha!

Thanks Nevine!

"I am from Bangladesh and have been wearing Malkha for some time. I went from Dacca to Kolkata to attend the Fair Trade Fair only to buy Malkha!

I waited

patiently from 11am till 3pm when the Malkha material came into the Fair Trade Fair and

before I knew it look at the crowd!!!

Sending you the pictures!"

Thanks Nevine!

Sunday, November 9, 2014

Autumn on the Eiffel Tower

From The Hindu, October 22, 2014:

Autumn on

the Eiffel Tower

Sangeetha Devi Dundoo

Shilpa Reddy to present a line

using hand-woven malkha fabric in Paris

Designers from 10 different countries, each with a

collection that represents their culture and heritage, showcased at an

architectural marvel makes for a winning fashion extravaganza. The forthcoming

J-Autumn Fashion Show at Eiffel Tower on October 31 follows in the series of

unique shows organised by Jessica Minh Anh.

Shilpa Reddy is the only designer invited from

India. “When I received the first email, I thought it was a prank, just another

random spam that comes into the inbox. A few emails later, I knew this was

serious. They had researched my work and were keen to have me on the show,”

says Shilpa.

The outfits have been couriered to Paris and Shilpa

is taking a short breather, before packing her bags and leaving to France.

“Every designer dreams of showing in Paris. I worked on the outfits until I was

satisfied and with each the design evolved each time,” she says, looking

forward to the window of opportunities this show will open up, both nationally

and internationally.

Keeping with the theme of the show, to give a

contemporary edge to a collection that will characterise ethnic weaves, Shilpa

chose the springy, breathable hand-woven malkha fabric. A fabric that’s

predominantly considered to be summer friendly, Shilpa says, has a unique

capability of keeping the wearer warm in winter. “I once wore a malkha shawl on

a flight when it was really cold and was surprised how warm it kept me. For

this collection, we are speaking of autumn in Paris. So I doubled-lined the

fabric,” she explains.

Outfits designed by Shilpa have mostly veered

towards structured silhouettes and she reasons, “Whether I design jackets or

blouses, I like them to be structured and the fabric shouldn’t be slouchy.” For

the J-Autumn Fashion Show, he has put together 16 ensembles, with some of the

looks having many layers. “It could be a skirt, top and a bolero jacket; then

there are palazzo pants and long trailing jackets,” she says.

The collection keeps in mind the sensibilities of a

global audience while using vegetable-dyed fabrics in mustard, black, indigo

blue and maroon with copper, silver and gold Indian embroidery.

Apart from being selected for the show, a morale

booster came from three of her outfits being used for the international

promotions of the show. “Jessica also asked if she could wear one of my outfits

to attend Manish Arora’s show at Paris Fashion Week. I was flattered. She also

complemented me on the extremely good finishes of the garments,” beams Shilpa.

One trademark of Shilpa’s lines has been immaculate finishes. “A number of

people have asked me why I care so much about the finish and if an outfit has

to be altered, would I redo the finish. Of course I will. A finish says so much

about the designing,” she states.

Hand-woven fabrics come with their own little

imperfections, be it in the weave or the tendency to bleed some colour. Shilpa

says, “I love the imperfections that come with anything handmade, which shows

the manpower and skill that went into it against a factory-made fabric. And

when we talk of a high-fashion line, buyers are definitely going to dry clean

the outfits, so there isn’t a need to worry.”

The J-Autumn Fashion Show

Conceptualised by fashionista Jessica Minh Anh, the

show will have a two-tiered outdoor 150-metre catwalk across the first floor of

Eiffel Tower. She has previously organised fashion shows at Grand Canyon

skywalk (USA), London’s Tower Bridge, Petronas Twin Towers’ sky bridge

(Malaysia), Costa Atlantica (Dubai) and Seine River (Paris).

Monday, November 3, 2014

The power of the handloom

Here is the full text of Uzramma's talk sponsored by the Lila Foundation at India Habitat Centre, New Delhi, on October 21:

Cotton cloth as continuity-

the power of the handloom

Do you remember the fairy tale of the

emperor’s new clothes?: Long long ago there was once a country that made the

best cloth in the world, in vast quantities, enough of it to clothe everyone in

the country, with enough left over to

send to many other countries. The other countries paid for that cloth in gold

and silver, making the weaving country one of the richest in the world. The kings

of that country wore fancy versions of that cloth, the poor people of that

country wore plain versions of the same. All the people, the milkmaids and

shepherds, the merchants and governors, the farmers and townsmen, all wore

versions of the cloth specially made for them.

One day some clever swindlers came to that

country and sought an audience with the emperor. Your majesty, they said, the

clothes you wear are not good enough for you. How can you wear the same as what

the fishermen and farmers of your country wear? Not only that, there are so

many different kinds of cloth made in your country that it is confusing. The cloth made in your country lasts for too

long, it is too soft and too comfortable. Don’t you know that the world is

changing and now things made by machine are the fashion. Cloth made by machine

wears out much sooner, it is not as soft, mass produced cloth is the same

everywhere, so everyone looks alike, it may be boring, but this is modernity.

The fantastic thing about this new way of

making cloth, they said, is that it is highly profitable for the owners of the

machines. It’s silly to make cloth on simple wooden looms in your villages,

from a bewildering variety of cottons; our expensive and complicated machines

that mass produce cloth in factories and need one and only one kind of cotton are a much better bet. This advantage

can be seen only by intelligent people like us, to all others it is invisible,

they said.

The emperor fell for this story and shelled

out sackfuls of gold and shipfuls of silver for the machines and for the cloth

made from them. The conmen dressed the

emperor in their machine made cloth, all

the time telling him how wonderful the new clothes were and how he now looked

like a real emperor. And for the next

two hundred years the people of that country waited for someone to say: That

cloth is rubbish. The cloth we made was much much better.

They are still waiting.

That fairy tale is the story of cotton

cloth in India. As in the fairy tale, India made enough cotton cloth to clothe

rich and poor in the whole subcontinent, with so much left over for export that

it was said to ‘clothe the world’. The world paid for this cloth in gold and

silver, which poured into India, not just into the pockets of the Adanis and Ambanis

but into the hands of the millions of

farmers who grew the cotton, the women who spun the yarn, and the weavers who

wove the cloth. India grew rich from its export, so rich that Europeans flocked

to India to make money for themselves, to ‘shake the pagoda tree’ as it was

said.

Today I’m going to remind you of the many

advantages of weaving on the handloom. I want to suggest to you that we should

look at the handloom not as an outmoded relic of the past but as a low-carbon

production technology for the

energy-stressed future. In my talk I’ll tell you about the grim reality

of cotton yarn spinning in India today, and what a dreadful fate awaits it. I

will also point out a possible brighter future – a possible, affordable and

rational future in which we safeguard the Indian cotton textile industry and

our rural livelihoods.

For much of my life I've been fascinated by

the story of cotton and cotton cloth making in India. I've spent the last 24

years working in this field. I’m part of

a small group of people who have been puzzling over the strange trajectory of the

indigenous cotton textile industry of India, during more than 20 years of

research combined with active involvement with handlooms. And I find that the

reality is as unbelievable as a fairy tale.

I’ll tell the story of the different bits of this industry by jumping from

country to country and century to century, backwards and forwards, because

that’s the way the story makes sense. In between we’ll hear some voices from

history. I’ll end with a possible roadmap for the future and I hope you’ll have lots of comments to add.

Simply put, India today is actively decimating

a sensible, energy-efficient low-carbon way of weaving cotton cloth on the

handloom, in favour of capital and energy intensive mechanized weaving which

only survives on subsidized electricity

and exploited workers. That’s the

powerloom weaving. And the yarn spinning industry too is in terrible shape. But

it is always the woes of the handloom and handloom weavers we hear about, while

the much larger woes of mechanized weaving

and spinning in India seem to be hidden, or ignored. To understand the strength

of the handloom, we need also to look into the dismal situation of the

mainstream cotton textile industry today.

The past, present and future of cotton

cloth making in India is fascinating. The distant past is extraordinary: the

Indian subcontinent clothed the world in cotton cloth for thousands of years.

The present is a mess, a real horror story.

The future depends on the choices we make. I believe the Indian cotton

textile industry has the potential to be a huge factor in India’s social and

economic well-being, if we take the right direction and recognize the power of

the handloom.

Making cotton cloth was the largest and

most important industry of the subcontinent for at least 2000 years, from the

time of Jesus Christ upto about the middle of the 19th century. Actually, we all know that. But do you also

know that

Today,

over 50 million’[1] people

in India grow cotton, gin cotton, bale and unable cotton, spin cotton yarn,

weave cotton cloth, sell cotton cloth, make clothes from cotton, export cotton,

yarn or clothes, or make oil and oilcake from cotton seed, and we’re not even

talking of the toolmakers, or including Pakistan and Bangladesh! But as if by magic, as if

it’s a fairy tale, this massive industry has become invisible!

Questions need to be asked, and the

first one is: How did the vibrant past

turn into the grim present? The answer seems

obvious: mechanization in the 19th

century made craft production unviable. But it wasn't as simple as that. There’s a crucial point here –The

mechanization was not just a matter of turning a hand process into a mechanical

one. It was a shift of fundamentals, of principles. It changed a flexible

technology into a rigid one. It changed a dispersed industry made up of

millions of small, scattered production centres into a centralized one, concentrated

in ‘industrial areas’ where the profits went into only a few pockets. [The Tatas, the Ruias, the

Sarabhais, the Ambanis all made their first millions in textile mills]. Mechanization

need not have been like that. It could have been quite different. You could

have had mechanization that was both flexible and decentralized, as hand

processing had been.

And

by the way the change didn’t happen automatically and smoothly, as many of you

are aware. It was made to happen all through the nineteenth century through unfair

trade practices by the English East India Company. A fascinating part of the

textile story:

Imagine yourself living in India in the

year 1820. You will remember from your

history lessons what was going on in India at that time. The last Mughal emperor

was weak. The Maratthas were defeated. Names familiar to us played prominent

roles on the Indian stage: Ranjit Singh of the Punjab, Baji Rao Peshwa of the

Maratthas, Wajid Ali Shah of Avadh. All of whom wielded enormous power. But the

most powerful ruler of them all was - the British East India Company. What was the Company? It was merely a large corporate entity, like

Walmart is today. But, backed by the government of Britain, it starts to rule over

large parts of India. The Company maintains an army, levies taxes and makes

laws. Nick Robins in his book The Corporation that Changed the World points out:“At its height, the Company ruled

over one-fifth of the world’s people, generated a revenue greater than the

whole of Britain and commanded a private army a quarter of a million strong.” .

Can you imagine a corporation like Walmart having its own army, levying taxes

and making laws! a corporate entity whose

sole purpose is to make a profit for its shareholders!

The trade of the Company, the ‘Honourable Company’,

as it was known, had an effect not just on the economies but also on the

societies of both England and India, an effect that is ‘hard to over-emphasize’

as a scholar of the subject puts it. Beginning in the early 1600s the Company imports

cotton cloth from India into England, where it becomes extremely popular because

its so washable: people prefer it to the locally woven cloth made from wool, linen

and mixed fibres; so much so that it destroys the English textile industry and

ruins the lives of English handloom weavers – while it makes English traders

and merchants rich (remember Napoleon 200 years later called them ‘a nation of

shopkeepers’!).

Cotton is the hinge on which artisanal cloth making turns to mass-production. The

first machines of the Industrial Revolution are machines for spinning cotton

yarn, machines that can be run by water or steam. This new industrial cotton textile production

needs to be fed cotton at an industrial rate, so cotton begins to be grown in

the newly colonized American continent, to

be imported into England from America, cotton that is grown and picked and

ginned by African slaves and the children of those slaves. “Indeed, so closely tied

were cotton and slavery that the price of a slave directly correlated to the

price of cotton” says a 2011 article in the New York Times, headed ‘When cotton

was king’.

“Slave produced cotton” is imported into England

to be mechanically turned into cotton yarn, the first product of

mass-production. And where is all that yarn to be sold? In India, of course, the

biggest cotton cloth weaver in the world. The Company carries the machine made yarn to

India, selling it cheap, undercutting locally made handspun yarn, and destroying

the hand-spinning industry of India.

..here is the first of two voices from

history –a short extract from ‘Representation from a suffering spinner’ a

letter printed in the Bengali newspaper Samachar

Darpan, in 1828:

“I am a spinner. [the letter says]. After having suffered a

great deal, I am writing this letter …The weavers used to visit our houses and

buy the charkha yarn at three tolas per rupee…

Now for 3 years we two women, mother-in-law

and I, are in want of food. The weavers

do not call at the house for buying yarn.

Not only this, if the yarn is sent to

market, it is not sold even at one-fourth the old prices. …They say that bilati yarn is being largely imported... I heard that its price is

Rs 3 or Rs 4 per seer. I beat my brow

and said, ‘Oh God, there are sisters more distressed even than I. I had thought

that all men of Bilat were rich, but

now I see that there are women there who are poorer than I'…They have sent the

product of so much toil out here because they could not sell it there. But it has brought our ruin only. Men cannot use the cloth out of this yarn

even for two months; it rots away. I

therefore entreat the spinners over there … to judge whether it is fair to send

yarn here or not.”

The devastation of handspinning was one part of the destruction of the

Indian cotton textile industry by the East India Company. There was more. There

were the taxes. Listen to Francis Carnac Brown on the subject of taxes in 1862.

Francis is a British cotton planter in India, on the Malabar coast.

“The story of cotton in India is not half

told, (he says), how it was systematically depressed from the ..date that

American cotton came into competition with it about ..1786, how ..one half of

the crop was taken in kind as revenue, the other half by the sovereign merchant at a price much below

the market price of the day …how the cotton farmer's plough and bullocks were

taxed, the Churkha taxed, the bow taxed and the loom taxed; …how it paid export

duty both in a raw state and in every shape of yarn, of thread, cloth or

handkerchief, ..how the dyer was taxed and the dyed cloth taxed, …how Indian

piece goods were loaded in England with a prohibitory duty and English piece

goods were imported into India at a duty of 2 1/2 percent. (He goes on to say): It is my firm conviction

that the same treatment would long since have converted any of the finest

countries in Europe into wilderness. ...”

That was the 19th century.

Now we’ll take a jump backwards in time,

the period that lasted from the time of Jesus Christ upto the early 19th

c. This was the period, lasting almost 2000 years, in which India clothed the

world. And it has its relevance to today.

There is an impression that the greatest

achievement of ancient Indian cotton cloth weaving was – as you must have heard- Dhaka muslins. Cotton cloth

woven so fine that that it had names like Woven

wind, Evening dew, Flowing water; So fine that when the Mughal emperor

Shahjahan chides his daughter the Princess Jahanara for being immodestly

dressed, she retorts that she has on seven layers of the stuff. Yes of course

this was a fantastic achievement… But in my opinion the greater achievement was

something else which I want you to pay close attention to, because I believe

that it is this that holds the key to the future:

‘Fustat textiles’ are pieces of Indian

cloth found in Egypt, carbon dated 9th

to 14th century. They are

thick, ordinary, coarse cloth. Ruth Barnes, the Textile scholar says these textiles “cannot claim fame as good examples of

outstanding craftsmanship”… but the significance for me is exactly that, that

it is coarse cloth, obviously for the

common man. India was unique in producing ordinary cotton

cloth for ordinary people on a vast scale

as a market-oriented activity from which millions of people derived their living. Making and selling cotton yarn and cloth were

economic activities which gave people an income. While cloth for the elites

was made in the ‘karkhana’ system, where yarn was given to weavers by a

‘master-weaver’ who marketed the finished product, cotton yarn and cloth was

sold through local markets to ordinary people, and both these kinds of cloth

were exported. According to my understanding making ordinary coarse cloth for aam admi was India

No

other region could do this. In China as

in our Northeast today cotton cloth was made as a household occupation. It was

only in the Indian subcontinent that it was a massive, market-oriented economic

activity. So viable, so embedded in

society that it has sustained for 5000 years. This is not just as a matter of

historic interest, but also is a vital clue to the future.

About

scale: Enough cotton cloth was made in India to clothe India’s own rich and

poor and for export both eastwards and to the west. In the

first century after Christ the Roman historian Pliny complains that India is

draining Rome of her gold - partly for spices, but mostly for cotton cloth. In 1610 Pyrard de Laval says about Indian cotton cloth “wherewith

everyone from Cape of Good Hope to China

It was the largest variety of cloth the world had

ever seen. "Every year ships arrive from Gujarat

on India's West coast… from Cambay a ship put into port worth seventy to eighty

thousand cruzados, carrying cloths of thirty different sorts" says Tome

Pires in 1515. [A cruzado was a Portugese gold coin]. And you find the

names of some varieties of these cloths in the Anglo-Indian dictionary known as ‘Hobson

Jobson’: Albelli, alrochs, cossai, baftas, bejutas, corahs,

doreas, dosooties, chhint, ginghams, jamdanis, morees, mulmuls, mushroos,

nainsooks, nillaees, palempores, punjams, susi.. and so on..

But

export was the smaller part. A huge part of the indigenous cotton textile

industry also went into local loops: cotton grown, spun, woven and sold

locally, through local markets. There is an account of a local weekly market at

Jamoorghatta, in a report dated 1867, by Harry Rivett-Carnac, Cotton

Commissioner for the Central Provinces, in which out of about 1400 stalls, 572

relate to cotton, yarn and cloth and 350 of the cloth sellers are non-weaver

castes: ‘Dhers, selling coarse cloth of their own manufacture’

It’s

amazing how little research has been done on this part of Indian textile

making. All the textile scholarship seems to be about export. No research on clothing

for the entire Indian population (250 million people in 1830)? That’s part of

the cloak of invisibility this industry wears! It’s not just for historic

interest that we need to look into this, but more important, to understand what

were our particular strengths and advantages that will be of use in the future,

that we can use today to make a viable, ecological and democratic cotton

textile industry, not one that just puts more money into rich industrialists’

pockets.

Now lets

go back to the 19th century let’s

see how the intervention of the EIC affected the growing of cotton in India:

Cotton

has been grown in India for 5000 years by smallholder farmers – as it still is.

Different varieties were grown in different parts of the country. They were

rain-fed and grown mixed with food crops of various lentils. Growing it with

other crops, did 2 things, it kept off pests and it replenished the soil. These

2 things made it possible to grow cotton in the same spot over millennia. But different varieties did not suit

mass-production, and Indian cottons did not suit the new yarn spinning machinery

that began to be invented in England in the early 1800s.

This

new way of spinning yarn was not in small scattered locations using wooden

equipment. it was concentrated in a few places and using huge machinery made of rigid steel. And what effect

did this change in spinning have on Indian cotton farms and farmer families? An

earth-shaking effect. Now cotton had to be aggregated, collected together, so

it had to be all of one kind, and that kind had to be one that could stand up to the harsh action of these

new steel machines. Indian varieties were too soft and their fibres were too

short. And so American cotton varieties were introduced into Indian cotton

farms by the East India Company, the Hirsutum varieties that had the long strong fibres the newly invented English

technology needed.

A

Colonel Prain writing in 1828 tells us:

“I have no doubt that the fine cotton produced near Dacca is one cause of the

superiority of the manufacture”, he says “nor do I think that any American

cotton is so fine, but then there can be no doubt that the American kinds have

a longer filament and on that account are more fitted for European machinery”.

The machines were heavy metal, bruising

and battering the delicate cotton fibres. Longer, stronger filaments took the

strain better, though they didn’t produce better cloth. That was it. Now that kind of cotton, became known as the best

cotton, not the cotton that made the best cloth. Instead of inventing a technology to suit the cotton, Walmart’s

ancestor, the EIC, changed the cotton plant to suit the technology. And nobody

cared that Desis and Americans grow in very different ways, one of which is

suited to Indian conditions, and one of which emphatically is not.

And

since then, till today, the definition of best quality cotton is what can stand up to harsh machine processing. .. and as machines are made to run faster and faster, nature is expected to keep up.

But

nature has its limits: and we’re feeling those limits now in the 21st

century. Cotton farmers today have only one customer -

the spinning mill, and all spinning mills today only have one kind of

machinery, the kind that demands ever longer and stronger staples. Growing American cottons does

not suit Indian soils or Indian climates, why because, as we say down South, the

American hirsutum cottons are shallow rooted, they cannot stand extremes of

climate.. You can never depend on the Indian climate - one year it rains too

much, the next year the rains fail. Desis have long taproots, which helps them

survive both too much and too little rain. Hirsutums need irrigation. Irrigation

creates humidity in which bacterial, viral, fungal diseases and pests thrive to

which cotton is particularly prone. The Bt gene is only

useful against a few varieties of caterpillar, its not a cure for virus or fungus, nor does

it prevent insect attack by thrips, aphids, mites,

mealy bugs.

Large-scale spinning broke up the

close relation of weaving cotton with growing cotton. After all, weavers and farmers were neighbours –

as they still are. Today between them

stands the modern spinning mill, to whom the cotton farmers must sell their cotton and from whom the

handloom weavers must buy their yarn.

A mill that forces farmers to grow the

kind of cotton that’s immensely risky for them …a level of risk that small

farmers cannot bear..the farmer suicides that have been happening particularly in

Maharashtra & Andhra Pradesh for the last 20 years, part of the largest

wave of suicides in history as Sainath reminds us. Many, possibly most, of

these suicides are of cotton farmers. But I don’t read anywhere that the

connection of cotton farmer suicides with cotton spinning technology has been

made.

Let’s take a

quick look at how yarn making happens in the mill: Cotton lint from the plant is first separated

from the seeds. In the 1800s, a new stage was introduced: after seed removal loose fluffy lint began to

be pressed tightly into bales. So tightly that it becomes as hard as a block of

wood, and needs an elaborate process and

huge machinery to get it back into separate fibres. Basically to its original

form. Its only after that the fibres are made into a loose blanket, then twisted and

thinned more in 3 stages into

yarn.

Of course

baling made sense when it was done to carry the cotton overseas to England. But

the unbelievable thing is that baling, bale breaking, bale opening and

reconstituting it into individual fibres are still integral parts of yarn

making! Even when cotton grows nearby! And these additional, energy-guzzling

stages that need huge infrastructure, are one of the main reasons for the

unviability of modern textile technology.

And of course

the reason why this industrial revolution yarn technology is unsuited to Indian

conditions is: it is uniform. It needs one kind of cotton and

one kind of cotton only. With this way of making yarn India loses what could its

greatest advantage, of being able to grow different kinds of cotton in different

regions. We need flexible yarn making technology that can adapt to different varieties of cotton.

Yarn-making

specifically suited to Indian diversity of cotton varieties is the missing link

in our otherwise potential, green, low-energy cotton-to-cloth production chain.

If we had that we could regenerate our diversity of cotton varieties. We still

have the handloom. Link the flexible technology of the handloom with diversity of

cottons through adaptable spinning and what will you get? A unique, hard-to-beat cotton textile

industry. It’s only the middle stage that’s missing. I suggest we rid ourselves of a

past “that lies upon the present like a

giant’s dead body” [to quote Nathaniel

Hawthorne] the burden of a rigid,

inflexible, energy-intensive yarn spinning technology.

And

how are the existing modern spinning mills of India doing?

Very badly. Today the mechanized

textile industry of India -mostly spinning- is on financial life-support from banks.

It has gargantuan bad debts which it is unable to repay. If you think Kingfisher

Airlines’s debts are enormous at 7000 crores, what d’you think of the mechanized

Indian textile industry's debt, at almost 2 lakh crores! Strange that we don’t hear these dire facts

about the mainstream industry, while its constantly dinned into us that

handlooms are in such bad shape. Its not

the handloom industry that has these huge debts! The fact is that the textile technology

that today is considered modern, both yarn spinning and mechanical weaving, is

“viable” only through debt-financing and on the back of an exploited

workforce. A kind of exploitation in

which we can’t compete with China. And because its on life-support its attracting

Vulture Investors.What are Vulture Investors? Vulture investors look for dead & dying industries: “There are

a lot of dead carcasses on the road, and the vultures are out sniffing,” says a

New York Times report after the 2008 Wall Street crash[2].

They’re here already. A recent headline in the

Economic Times [July 30 this year] says the US’ W L Ross plans to invest in the

Indian textile sector. Has anybody heard of Wilbur L Ross? He is known in the

US as the dean of vulture investors. And now this canny investor has already taken the first steps

towards swallowing up the Indian Textile industry. Its my guess that he is poised to flood the great Indian market with

low-cost yarn spun in China and Vietnam. He could be the 21st

century avatar of the East India Company, destroying Indian spinning again 200

years later! So it becomes urgent to develop small-scale spinning, because the only kind of industry that can stand

up to Wilbur L Ross and his ilk is

a dispersed one, with small investments in scattered infrastructure.

This is a

plea to the country’s scientists and technologists to put in the research and

development needed to work out small-scale cotton yarn making for the future,

specifically suited to Indian cottons and to the handloom: smaller, flexible

machinery that can be run by alternative energy and that can process different

cotton varieties. We could then take the

cotton textile industry out of ghettos

and industrial centres where it is today and put the whole field-to-fabric

production chain in thousands of locations next to cotton fields. Cutting out the

exploitation of powerloom workers. Saving energy by cutting out transport,

cutting out baling. With smaller investments in small-scale infrastructure. An industry

that can be owned by producer collectives. A truly modern, democratic textile

industry on a vast scale, suited to an energy-stressed future. That would bring

smiles and not tears to cotton farmers and weavers - whose combined numbers

make up a substantial part of the Indian population.

And finally:

handloons & climate change. A recent report of the Global Commission on the economy & Climate change, which has

members from the World Bank, Unilever, and

the Bank of England, says that investments in low-carbon technologies will stimulate

rather than hamper economic growth. That makes India several steps ahead on this score – we don’t even need to invest vast sums - we already have a low-carbon

weaving technology in all parts of the country, complete with its huge bank

of equipment and skills. This means that we can have our cake and eat it too and share it around: by promoting hand weaving we can claim

international credit for setting up a low-carbon textile industry, we can make

good cotton cloth for ourselves and for export and spread the profits of textile making among a large part of

our population.

Weavers

and farmers must be re-connected through small-scale spinning – not by harking

back to the past, but in a modern, viable, feasible way, building producer-owned,

flexible technologies around the handloom rather than replacing it.The handlooms are there, the weavers are there,

the cotton farmers are there waiting to be offered an honourable life in return

for providing us energy-efficient cotton textile production!

As a

post-script I’d like to add that the Malkha initiative in which I have been

involved for some years has taken the first small steps in this direction, so

far with some success.

Sunday, October 12, 2014

Dire straits

We feel like prophets of doom crying in the wilderness: No-one seems to be concerned about the dire straits the Indian textile industry is in. Outstanding debt is reaching 2 lakh crore rupees! How is the industry going to get out of this hole? And what does it mean for handloom weavers?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)